Summary

International Human Rights Day offers an opportunity to examine fundamental rights in Myanmar and reflect on what may happen next year, in 2026. But before looking to 2026, Human Rights Myanmar’s previous predictions for 2025 are reviewed against reality.

Jump to:

Past predictions vs. reality

Prediction 1 (Correct): Transitional challenges for NUG and ethnic groups: As resistance groups consolidated control in areas like Northern Shan and Sagaing, reports emerged of fragmented legal systems and occasional power abuses. While the NUG attempted to enforce codes of conduct, governance remained inconsistent and often male-dominated at the local level.

Prediction 2 (Correct): Escalating military atrocity crimes: The military continued relentless airstrikes, particularly in Rakhine and Sagaing. Collective punishment tactics, including village burnings, intensified throughout 2025 as the military launched clearance operations to secure areas for the December elections.

Prediction 3 (Correct): Deterioration of civic space: The military activated the Cybersecurity Law (2025) and deployed Chinese surveillance tech to monitor communications. Myanmar solidified its status as a global hub for opium production and cyber scams, generating illicit revenue to offset sanctions.

Prediction 4 (Delayed): Impact of ICC actions: While the ICC judges had not issued a warrant by late 2025, an Argentinian court issued a historic arrest warrant in February. However, this legal pressure did not deter China from deepening engagement with the military ahead of the elections.

Prediction 5 (Mixed): Exiled civil society under pressure: Thailand unexpectedly granted legal work rights to long-term refugees, easing some deportation fears. However, the prediction on funding was accurate as severe cuts by major donors like USAID and Sweden forced many CSOs and media outlets to downsize.

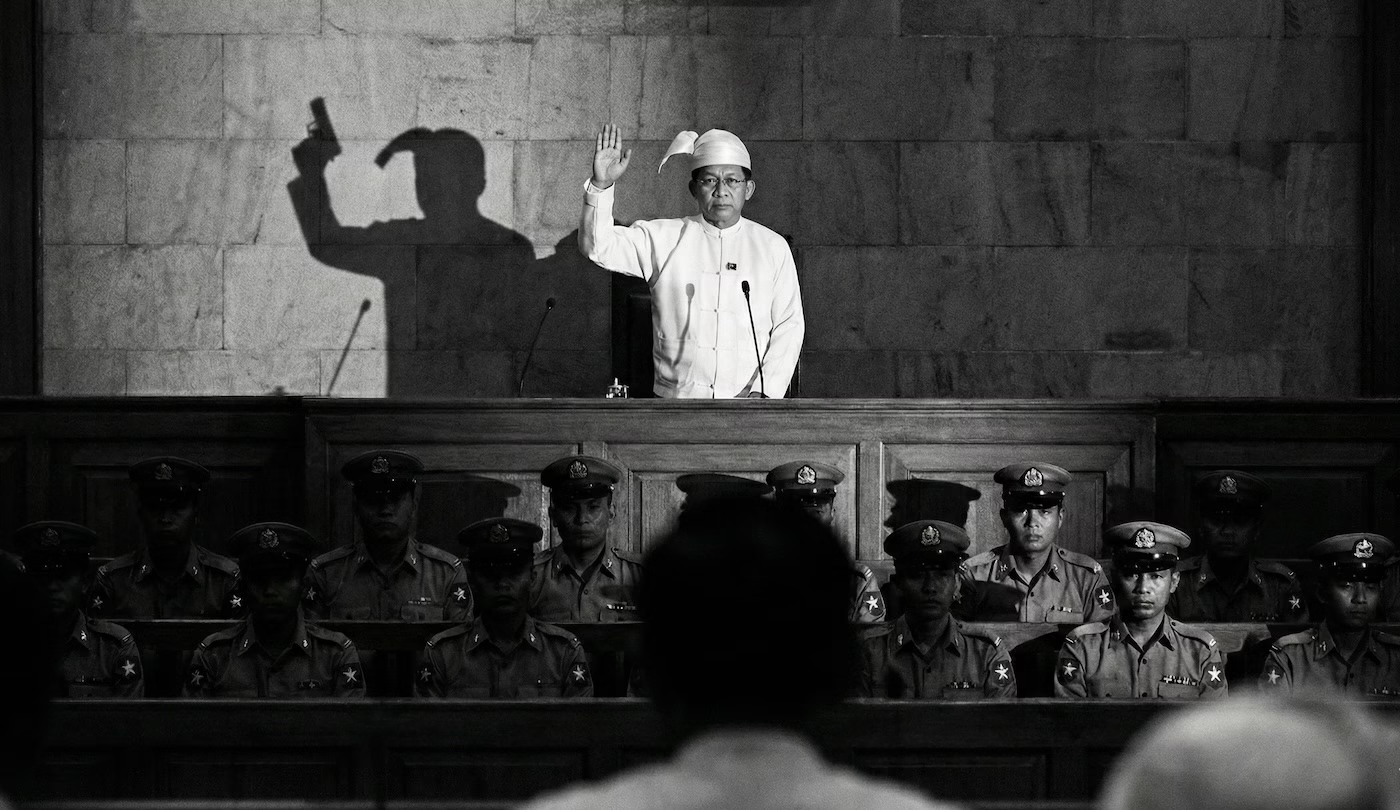

Some of these 2025 predictions will continue in 2026. The military’s so-called “election”, due to start on 31 December 2025 and continue through the middle of January 2026, will also lead to further developments. The following analysis forecasts human rights implications for 2026 if the military installs a proxy civilian government similar to the transitions of 1974 and 2010.

Prediction 1 for 2026: From martial law to “lawfare”

The inauguration of a proxy civilian government will mark a shift from emergency decrees to “lawfare”, where the judicial system is used more systematically against opponents.

Mirroring the 1974 reforms, the government will move away from more obvious violence to primarily enforcing laws like the Counter Terrorism Law (2014) and Penal Code (1861) through highly dependent courts. This strategy projects due process and a sort of normalcy while criminalising dissent. It will replace arbitrary detention with politicised criminal convictions that carry the weight of legal finality, undermining rights to fair trial and liberty. It will also give proxy civilian leaders the excuse that they do not want to “interfere with judicial independence”.

2. The Thai model of repression

Seeking international legitimacy, the proxy government will likely shift from mass incarceration to strategic targeting and disproportionate sentencing.

Tactics will mirror Thailand, where specific targets receive massively disproportionate sentences instead of filling prisons with thousands of protesters. Courts will hand out decades-long sentences for minor offences like social media posts, creating a chilling effect that limits dissent without the logistical cost of mass detention. Furthermore, while detaining thousands shows an illegitimate government, imprisoning a few “only” shows an authoritarian government.

3. Automated warfare and sustained conflict

The post-election landscape will not see de-escalation but an intensification of automated warfare fuelled by renewed foreign support.

Resembling the 2010 resumption of Kachin fighting, the 2026 election will embolden military campaigns rather than seek compromise. A disputed election victory allows the military to normalise relations with China, facilitating transfers of more weapons, advanced drones, and loitering munitions. This technological escalation threatens the right to life by increasing the likelihood of indiscriminate attacks and removing humans from the killing process.

4. Technical enclosure of the digital space

To maintain economic legitimacy, the incoming proxy government will replace crude internet shutdowns with advanced surgical censorship.

Unlike blunt shutdowns, the government will utilise the Cybersecurity Law (2025) and new Deep Packet Inspection technology to block encrypted traffic and VPNs while keeping other digital tech operational. People’s attempts to access blocked mass platforms like Facebook will reduce as the public splinters into different spaces. This mimics the Chinese model, where access to independent information is throttled while the digital economy functions, severely infringing upon privacy and access to information.

5. Integrated online and offline surveillance

The 2025 election and census provided data to upgrade legacy control mechanisms into a comprehensive surveillance network.

Authorities will integrate the Person Scrutinisation and Monitoring System with biometric SIM registration, effectively digitising the SPDC-era guest registration system. Local officials and police will cross-reference physical checks against central digital records to screen people and conduct targeted raids based on data discrepancies, negating privacy and restricting movement for anyone wishing to reside anonymously.

6. Division of civil society

A proxy government will trigger some return of international aid, forcing a split in civil society similar to the post-2010 transition.

Strict enforcement of the Organisation Registration Law (2022) will compel groups to register as service providers or face prosecution. Some civil society organisations will choose to register and change their work to do so, while others will choose their independence and remain excluded. As in 2010, donors engaging with the government will likely, intentionally or otherwise, compel civil society to sanitise development work, stripping rights-based approaches. This policy undermines freedom of association and excludes organisations that refuse to remove rights from their work.

7. Declining voices due to aid withdrawal

The simultaneous withdrawal of major donors threatens to dismantle the independent media and civil society infrastructure.

With USAID funding having ceased and Sweden phasing out assistance by June 2026, the pillars of support for exile media and independent civil society groups are collapsing. This loss of funding will drive a sharp decline in independent reporting and information flows about what is happening in Myanmar, particularly outside the mainstream. The impact is concrete, with women’s groups losing safe houses and rights defenders losing digital security, infringing upon freedom of expression and ceding narrative space to state propaganda.

8. Diplomatic normalisation and transnational repression

An “elected” proxy government will provide regional neighbours with diplomatic cover to re-engage, treating opposition members as criminals rather than political actors.

Mirroring 2010, this shift facilitates informal transnational repression where neighbours hand over dissidents without due process. The Myanmar government will demand the return of individuals, treating them not as refugees fleeing a coup but as criminals fleeing a democracy threatening the right to asylum and violating non-refoulement principles.

9. Entrenchment of nationalist supremacy

As violent control dissipates, it will be replaced by administrative systems prioritising Bamar Buddhist male interests once again, while undermining women and minorities.

Shifting to social engineering, the proxy government will strengthen the Bamar Buddhist man as the central figure of national identity. Revitalising Thein Sein-era approach seen in the Race and Religion Protection Laws and using the Constitution to exclude women from high office, the regime will upgrade its newly digitally-powered citizenship scrutiny to marginalise non-Bamar groups, stripping them of legal status without physical force.

10. Platform fatigue and algorithmic surrender

Major technology platforms are expected to reduce their crisis response resources as the conflict drags on and the regime presents a civilian face to the world.

Companies like Meta and Google may treat the new administration as a legitimate government, which could lead to a rollback of the special policies put in place after the 2017 Rohingya genocide and the 2021 coup. This platform fatigue, combined with the removal of ban designations for military entities now rebranded as civilian ministries, will likely reopen the digital space to coordinated attacks, doxxing, and propaganda unchecked by algorithmic safeguards, threatening the right to safety and non-discrimination.

Recommendations

The international community must move beyond condemnation and take specific action to counter these trends.

- For ASEAN and UN Member States: Refuse to recognise the 2025 elections or the resulting government as legitimate. Do not use the transition to a nominal civilian administration to normalise relations or ease sanctions. Diplomatic engagement must be conditional on verifiable progressive policy changes rather than procedural milestones.

- For arms-supplying States: Do not use non-credible elections to justify resuming or expanding military transfers. The installation of a proxy government does not alter regime illegitimacy or absolve suppliers of complicity. Halt transfers of lethal aid surveillance infrastructure and advanced weaponry enabling automated targeting of civilians.

- For international donors: Maintain funding for rights-based approaches despite restrictions. Resist pressure to “depoliticise” aid or strip human rights language from proposals, as this abandons civil society. Ensure support reaches organisations refusing to register with the regime.

- For technology companies: Sustain resources to remove military propaganda and coordinated attacks. Do not scale down content moderation under the false assumption of stability. Continue protecting at-risk users and resisting regime censorship attempts.